The hyped headlines churned out by media outlets haven’t been able to agree on what podcasting’s path to popularity has been. But one thing is completely clear: podcasting is definitely a big deal right now. Serial, which debuted last October and has been called podcasting’s first real hit, introduced many to the medium. New shows and subscriptions seems to be springing up everywhere.

But what really is the deal with podcasting? Are the articles celebrating its return accurate? Is podcasting an overnight hit as so many have proclaimed it to be, or is there more to its success story?

We decided to put aside the hype and delve deep into the true history of podcasting — and what we found may surprise you.

The First Rise (And Fall) of Podcasting

Christopher Lydon started out his career in journalism covering politics for The New York Times 1970s. He later moved on to anchor a weeknight local news show in Boston and then hosted his own public radio show before becoming a fellow at Harvard Law School‘s Berkman Center for Internet & Society in 2003.

While at Harvard, Lydon met Dave Winer, a software and internet whiz who had already created a blog platform for the Harvard Law School. Lydon reached out to Winer about setting up his own blog to use while he was a fellow at Harvard. However, due his background in TV and radio, Lydon also wanted to record and share the in-depth interviews he was conducting with figures such as Julia Child, instead of sticking to the usual text-only blog posts.

Winer devised a special version of an RSS feed that could pull in the MP3 files of the interviews alongside the more traditional text posts. To debut the new feature, Lydon interviewed Winer himself and released the recording to his blog in July 2003. That interview became the first podcast ever. (Twelve years later, Lydon is still going strong with Radio Open Source, a public radio show and podcast that he officially started in 2005.)

However, the word “podcast” wasn’t used until February 2004, and journalist Ben Hammersley is credited with coining the term in an article for The Guardian. In the story, Hammersley debates several names for the new audio phenomenon, including “podcasting” and “audioblogging.” Podcasting was the name that stuck, in part because the portmanteau so neatly summed up the nature of the format. “Cast” came from radio broadcasts, and “pod” came from the iPod, Apple’s game-changing music player, which was just three years old at the time.

Beyond making the iPod, Apple also contributed to podcasting’s development by incorporating podcasts directly into its emerging audio empire. In June 2005, the company boldly announced in a press release that “Apple Takes Podcasting Mainstream” with the 4.9 version of iTunes. While the claim was perhaps a bit premature — experts were still debating if podcasts had truly gone mainstream in 2014 (more on that later) — building podcasts straight into iTunes eliminated the need for a separate aggregator and made it easier for users to subscribe and listen to them.

“Podcasting” was also named Word of the Year in 2005 by the editors of the New Oxford American Dictionary, beating out other entries like bird flu and IED. If the makers of a dictionary were paying attention, then clearly podcasting had secured its place in the public’s mind. So of course, creators soon began to look for a way to monetize podcasts. The Ricky Gervais Show became the first major podcast to charge people to download episodes, beginning with the second season in early 2006. More and more podcasts began to implement the paid subscription model, and some began to experiment with incorporating advertisements as well.

The release of the iPhone in 2007 only made it easier to listen to podcasts (and therefore to make money off of them). Finally, you could manage podcasts directly on the device instead of having to download them on your computer and then manually sync them to your iPod using a cable.

However, the podcast fad began to taper off towards the end of the 2000s, right around the time that the USPTO controversially awarded VoloMedia patent 7,568,213 for “the fundamental mechanisms of podcasting” in 2009. The rise of YouTube and other video platforms and of music streaming services like Spotify created plenty of competition for listeners’ ears. Why listen to a podcast when you could choose any song on demand or watch a hilarious cat video?

And just like podcasting was in, it was out. Sure, some people continued to download and subscribe to them, but podcasts didn’t inspire the same excitement they once had, and there were just so many other entertainment options available. In comparison, podcasts now had a retro feel to them, and not the good kind of retro, giving off the vibe that they would soon go the way of AIM and the Sony Walkman.

And then a couple years later, podcasts were back with a vengeance.

The So-Called Podcast Renaissance

The makers of Serial had no idea that their show would help spark the resurgence of podcasting when they released its first two episodes on iTunes on Friday, October 3, 2014.

Or was Serial actually the main cause?

It’s tempting to point to Serial as the chief instigator of the podcast renaissance. After all, it makes sense that the show’s wild (well, wild for podcasting) popularity would inspire others to both make their own quality podcasts and listen to more shows.

However, the so-called “podcasting renaissance” actually began before Serial debuted in the fall of 2014. In late July 2013, more than a full year before Serial, Apple announced that it had passed the one billion podcast subscription mark in iTunes. The next month, USA TODAY ran an article proclaiming “Remember podcasting? It’s Back — and Booming.” TIME published another story on podcasting’s comeback just two weeks later, explaining how the medium was drawing both listeners and advertisers alike.

Podcasts such as comedian Marc Maron’s WTF and The Talk co-host Aisha Tyler’s Girl on Guy had also attracted dedicated audiences by the time Serialdebuted its first episode over the airwaves of This American Life. So if it wasn’t Serial, what did cause the podcasting renaissance?

The answer is perhaps far less gripping than Serial’strue life crime drama, but no less important: the evolution of technology. And not just podcasting recording-specific technology (though of course that helped) but also the entire ecosystem of listening on the go.

Prior to the original iPhone’s release in 2007, listening to a podcast was a chore. You had to download the audio file to your computer, then sync it to your device (probably an iPod) with a cable. Unlike a song, which you only have to sync once, you had to complete this cycle every week as new episodes were released. Not to mention routinely sort through your library and manually delete the old podcasts you’d already listened to make room for more.

Once smartphones came out, you could finally start downloading podcasts directly to your device. The various cloud-syncing services also made it easier to keep track of what you had listened to and what you hadn’t. If you listened to a podcast on your desktop, it would also be marked as completed on your phone automatically (and vice versa).

But the real kicker was the emergence of Bluetooth and other forms of technology that made it easier to listen to podcasts in the car. Approximately 44% of all radio listening occurs in the car, and the average commute length is 26 minutes one way, giving normal working Americans nearly an hour a day when their hands are occupied but their ears and minds aren’t — the perfect time for listening to podcasts.

Streaming technology in cars wasn’t perfect (in fact, it’s still got a long way to go), but as Bluetooth and other similar technologies entered the mainstream, it became more and more convenient to listen to audio in your car. No longer did you have to hunt for a cable that fit your smartphone and your case, or try to troubleshoot a static connection as you maneuvered the car with one hand.

Sure, you could play your own music or try to find a channel you liked on Sirius XM, but podcasts presented the perfect way to turn the downtime of driving into a more productive period, or least a period of conscious entertainment consumption. You could download whatever podcast you wanted and listen to it whenever you wanted, instead of having to tune in to whatever song or show was airing at the time.

Tech advancements also benefited podcast producers. It’s now possible to produce a decent quality recording using a computer, microphone, and a few other items, instead of the entire room of specialized radio equipment it used to take. Furthermore, you didn’t have to employ an entire staff of specialists in order to operate said audio equipment. (Plus, since podcasts are just audio, they’re often way cheaper to produce than a video or other type of content of the same length.)

Clearly, Serial was released at a fortuitous time. Technology had progressed to the point when both producing and listening to a podcast was fun instead of a hassle, and podcasting was slowly re-entering the public consciousness as a valid (and even cool) form of entertainment.

So if Serial didn’t singlehandedly spark the podcast renaissance, what did it do?

Serial: The Not-Quite Savior of Podcasting

Had Serial been released a couple years earlier, it’s doubtful that the show would have become so crazy-popular because of the state of technology at the time. However, while the audience for podcasts was certainly growing at the time that Serial was released, podcasting wasn’t really mainstream yet.

Crucially, part of Serial’s appeal was irrelevant to the fact that it’s a podcast. The format of podcasts definitely lends itself to telling such an audio-heavy story as Serial’s. But the storyline would have been compelling whether it was told through a book, video, podcast, or otherwise: A high school student is mysteriously murdered and the supposed killer — her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed — is tried and sentenced, only for the case to slowly come apart under investigation 15 years later.

In fact, Serial’sstoryline was so gripping that it inspired several companion podcasts, including Undisclosed: The State v. Adnan Syed, which breaks down the facts and evidence of the state’s case against Syed. Undisclosed, which is made by a totally different team than Serial, debuted its first episode on April 13 of this year and has released eight full episodes so far. Serialitself has announced that it will produce at least two more seasons, though each one will focus on a different narrative instead of continuing with Syed’s story.

Serial’s longform narrative encouraged listeners to consistently check back each week, unlike (say) weekly radio program This American Life, which helped bring Serialinto existence with financial and editorial support. This American Life is indeed available to download as a podcast, and it’s currently the top podcast in iTunes right now (it’s consistently been one of the more popular ones for a while). But it also airs on WBEZ Chicago as a live radio show, which puts way more narrative constraints on what it can and must accomplish.

As a result, This American Life focuses on just one theme or storyline per episode, and this changes from week to week. Forget to tune in one week and you’ll miss out on a great piece of audio content, but it won’t fundamentally impair your understanding of next week’s program. But miss a week of Serialand the following episodes won’t make sense, creating an incentive for followers to listen to the podcast regularly and sequentially.

In contrast to its parent show, the flexibility of the podcast-only format allowed Serialto develop one narrative over the months. In addition, Serial’sproducers could also make the episodes as long or as short as they needed, instead of being confined to an exact one-hour block each week; episode lengths range from 28 to 56 minutes. Serialunited the perfect storyline with the perfect medium.

Both the numbers and the press coverage proved just how popular Serialwas (and is). Only six weeks after its debut, it had already been downloaded or streamed from the iTunes Store more than 5 million times, becoming the fastest podcast to reach that milestone, and David Carr from The New York Times hailed it as “podcasting’s first breakout hit.” (Nevermind that this first hit was eleven years in coming, practically an eternity in the modern age of advancing technology.) This April, the show even became the first podcast ever to be awarded a prestigious Peabody Award. Serialmight not be solely responsible for the podcast renaissance, but it was certainly the first podcast to capture the public’s attention so completely.

Looking Forward

It’s funny how the popularity of a phenomenon often rises in proportion to the lawsuits concerning it. Indeed, people rarely try to make money off of something no one cares about, and this was certainly true for podcasting. Perhaps the most well known podcasting “patent troll” is Personal Audio LLC, which had been granted several podcast-related patents over the years. However, it wasn’t until 2013 — just as the podcast renaissance was beginning — that the company actively began trying to enforce the patents.

Personal Audio started bothering podcast-makers, claiming that it had invented podcasting and that the independent producers had to pay the company a licensing fee or be taken to court. The most high profile target was comedian Adam Carolla of The Adam Carolla Show, which Guinness World Records named the most downloaded podcast ever in 2011. Carolla ended up settling with Personal Audio, but only after spending more that $650,000 to defend himself.

Then in April of this year, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office overturned five key provisions of Personal Audio’s main podcasting patent. The patent can now no longer be used to sue podcasters, which is a major victory; after all, part of podcasting’s success has been due to the ability for small teams to make episodes quickly and cheaply, something that expensive licensing fees would surely hinder. Podcasting is safe from patent trolls and free to keep growing at a rapid pace, at least for the moment. So besides patent litigation (or the lack thereof), what else could affect the development of podcasting in the near future?

One factor that is unlikely to change is podcasting’s ability to draw dedicated fans. The people who do regularly follow to podcasts listen to a lot of them, and podcasting makes up about a quarter of all audio they listen to. The sticky, sequential nature of podcast content tends to draw people back week after week. Fanbases also build communities around podcasts they love, much as people do for TV shows or book series — there’s even a thriving subreddit for Serial.

On a less warm and fuzzy note, podcasts also make financial sense for producers. Because of audience engagement, ads rates for podcasts are relatively high compared to other mediums like radio or video, usually between $25 and $40 per one thousand listens (called CPM, or cost per mille).

Host-read ads, which are often read in the style of the show, are particularly intriguing to advertisers. Since the hosts don’t usually break character, the ads they read as seen as more authentic than ordinary sponsored spots. For instance, in July 2014 Marc Maron fully admitted to not playing video games before reading an ad for (you guessed it) the online video game World of Tanks. The episode also featured an interview with comedian Mike Myers, and become of one of Maron’s most downloaded episodes of all time, giving World of Tanks a huge boost in the process, despite Maron’s confession.

In a more shocking example of “authenticity,” in early February Bill Burr opened an episode of his Monday Morning Podcast with this memorable Valentine’s Day endorsement of Sharri’s Berries: “Yeah, get [your significant other] something unique. Get her something you and fucking four million other people are going to get.” While Sharri’s Berries admitted the ad’s tone wasn’t really on-brand for them, the company acknowledged it was definitely in line with Burr’s style — and did they mention the endorsement was ROI positive for them anyways?

Experiments with podcasting advertising are in their beginning stages now, but so far they’ve proved that there’s at least the possibility of revenue. However, podcasting’s hold is far from absolute. Android phones, which make up more than half the smartphone market in the U.S. right now, don’t have a native podcasting app. (Apple, whose native podcast app can’t be deleted from the iPhone, comes in second with a market share a little over 40%.)

And while the number of Americans listening to at least one podcast a month has risen steadily over the past years — it reached 17% in 2015, which works out to about 46 million people a month — this figure pales in comparison to the 93% who listen to music. Current podcast subscribers might be devoted to the format, but there are many others out there who have yet to be converted. Compared to music or video, podcasting is still small fry.

To those who have been suddenly initiated into this “new” world of audio through Serialor another show, podcasting’s popularity can seem like it came out of nowhere. But all the hype notwithstanding, over the past decade podcasting’s growth has been slow and steady with few notable spikes, and its future trajectory will likely follow this pattern as well. Consistency has been the key to medium’s current success. Indeed, that 2013 USA TODAY article that claimed postcasting was “back and booming” would have been far more accurate if it was headlined like this article from The New York Times instead: “Podcasting Blossoms, but in Slow Motion.”

To paraphrase the infamous Mark Twain quote, reports of podcasting’s rise and fall (and rise again) have been greatly exaggerated. Truthfully, the podcasting renaissance seems to have more to do with changes in public awareness than changes in actual listeners and subscribers. However, there’s no denying that podcasting’s growth has been trending upward, even if it’s not quite as dramatic as some media outlets make it out to be. And all evidence, from statistics to Serial, only points to podcasts becoming more popular.

Of course, if enough media outlets and influencers continue to trumpet podcast’s return, perhaps there will indeed be a legitimate spike in listens and subscriptions. Convince enough readers that podcasting is having a major resurgence, and they’ll begin swarming to it in droves, creating the comeback they were told existed in the first place.

The numbers don’t show this happening — yet. But there’s a chance that it might in the near future. So if you’re thinking about starting your own podcast, you should probably do it now. If you wait, who knows how many new Serials you’ll have to compete with in the future?

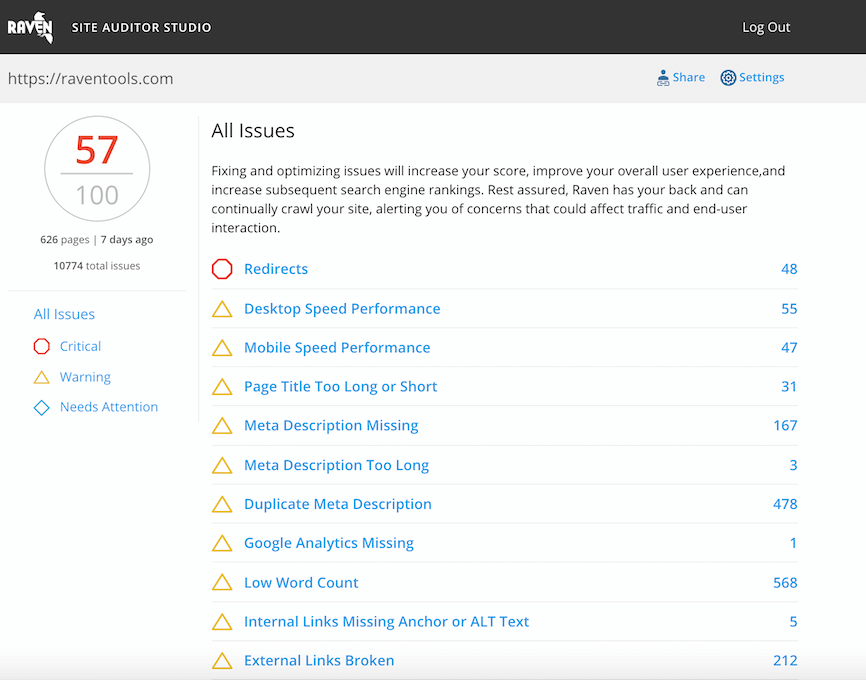

Analyze over 20 different technical SEO issues and create to-do lists for your team while sending error reports to your client.